American Dining Paintings

Jeff Bliumis’ Ways of Seeing

by Ksenia M. Soboleva

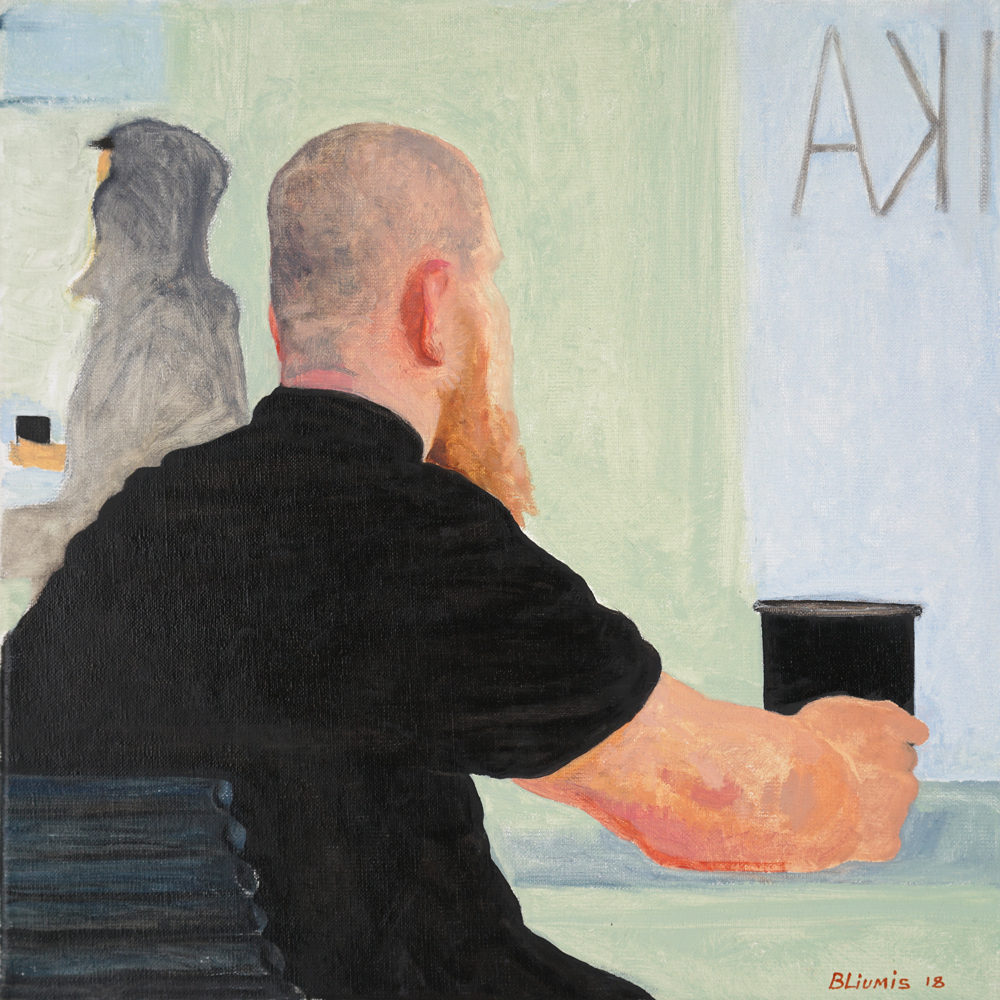

Throughout his artistic career, Jeff Bliumis has been engaged in an ongoing exploration of various media, ranging from painting and sculpture to socially engaged conceptual projects.

Using art as a way to make sense of the inherent strangeness of being, the Moldavian-born artist has decidedly spent the past four years evolving his practice of painting and drawing. When one of Bliumis’ large bronze sculptures fell on his stomach and landed him in the hospital in 2015, the artist developed a body of work that has marked his representational strategies since. Aptly titled View from Below (2015),

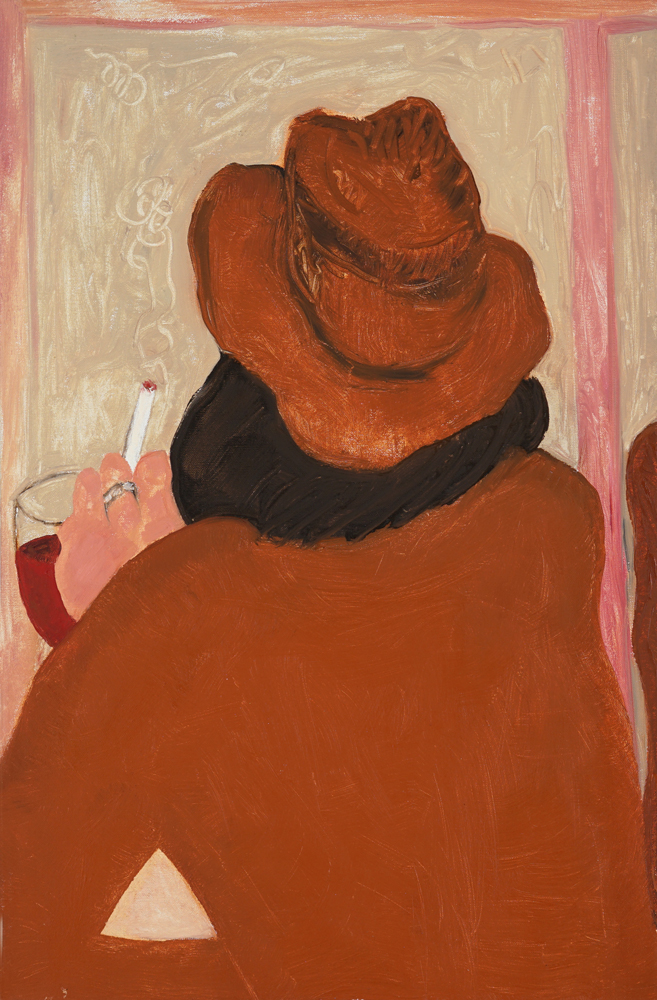

the series that resulted from his tenure in the hospital is characterized by a colorful palette, unfinished technique, and an exaggeration of forms; these are not merely stylistic choices, but reflect Bliumis’ genuine perception of reality as a result of the incident. Since then, Bliumis has further developed his signature style that cuts against the grain of figurative representational strategies. Employing flattened perspective and a distortion of forms, Bliumis brushes the oil paint out to such an extent that it appears sheer, revealing the white canvas underneath and thereby leaving a visible trace of his artistic process. In Bliumis’ world, limbs become awkwardly elastic (Lucy, 2018), bars are invaded by aliens (Upstairs, Downstairs, 2018), and fish somehow appear more human than the chefs who are about to cook them (Miska, 2018).

From an art historical point of view, the debt to Expressionism is palpable, and Bliumis confirms to have been in awe of Austrian and German Expressionists such as Egon Schiele, Otto Dix and Oskar Kokoschka, throughout his lifetime. Yet, while the artists of this early 20th century movement imbued their art with a great amount of emotion to express the increasing frustration they felt with the human race, Bliumis’ interpretation of the subject contains a cool distance that sets his work apart from the heritage on which it builds.

The barista appears to be making coffee with her eyes firmly closed (About, 2018), as two nuns assertively stare into the distance while having a meal seated next to each other (Blue Nuns, 2017), and a figure with lavish black curls glumly turns away to check on a reservation (Reservation, 2018). Mainly portraying strangers he encounters while going about his everyday life in New York City, Bliumis’ paintings and drawings range from close-up views of individuals, to crowded scenes.

The subjects reflect New York’s exploding diversity, and Bliumis’ use of reductive forms often leaves their gender ambiguous. Ranging from restaurants to hair salons, the setting is usually one that fosters, or even requires, social interaction. When looking closer, however, one notices that in the majority of Bliumis’ works the subjects are barely interacting with their surroundings. Oftentimes, their eyes are either closed or covered by hair, their gaze either lowered or averted, and on some occasions they are turned away altogether. While these figures occupy various bustling worlds marked by a promise of encounters, they rarely engage with one another; instead, they gaze in different directions, avoiding eye contact. One could interpret this absence of interaction as the artist’s commentary on our digital age, clutching to his sketchbook while others are absorbed by their phones, yet this would be a lazy argument. Rather, Bliumis’ work raises larger questions around the relation between the spectator and the spectated.

In Ways of Seeing, the celebrated art critic John Berger argues that it is the reciprocal gaze that provides proof of our existence: “Soon after we can see, we are aware that we can also be seen. The eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are a part of the visible world. If we accept that we can see that hill over there, we propose that from that hill we can be seen.” With this in mind, Bliumis’ negation of looking as a reciprocal act seems to suggest that his figures are detached from the visible world, unattainable not only to each other, but more critically, to the artist set out to portray them.

Indeed, Bliumis’ work exposes an undividable gap between the artist and his subject, an impossibility of connection reminding us that we are far past the outdated notion that artists walk the earth “capturing” the essence of things, without needing much consent or context. The last few years, in particular, have witnessed a long overdue assessment of the boundaries between spectatorship and objectification. In his portrayal of strangers, Bliumis balances on the fine line between these two; Negating the source of his figures so that they become unrecognizable,

Bliumis does not try

to fool anyone into thinking that he has captured the essence of his subjects’ existence. His work is powerfully refreshing in its abandonment of the grand gestures of expressionism, a rhetoric that many male painters still hold on to. Instead, Bliumis is engaged in an unassuming exploration of the ways in which bodies occupy social space, and the humorous scenes that can arise from these non-encounters.