Service Paintings

Jeff Bliumis, Gotta Serve Somebody

by Irena Popiashvili

If there is a defining message by Jeff Bliumis, it is to make us think about how much — and how little — we appreciate ‘service,’ the critical role that service workers play in the day-to-day life of modern societies. The way he achieves this makes that message even more intriguing — because Bliumis has somehow managed the contortion of creating portraits that are not really portraits.

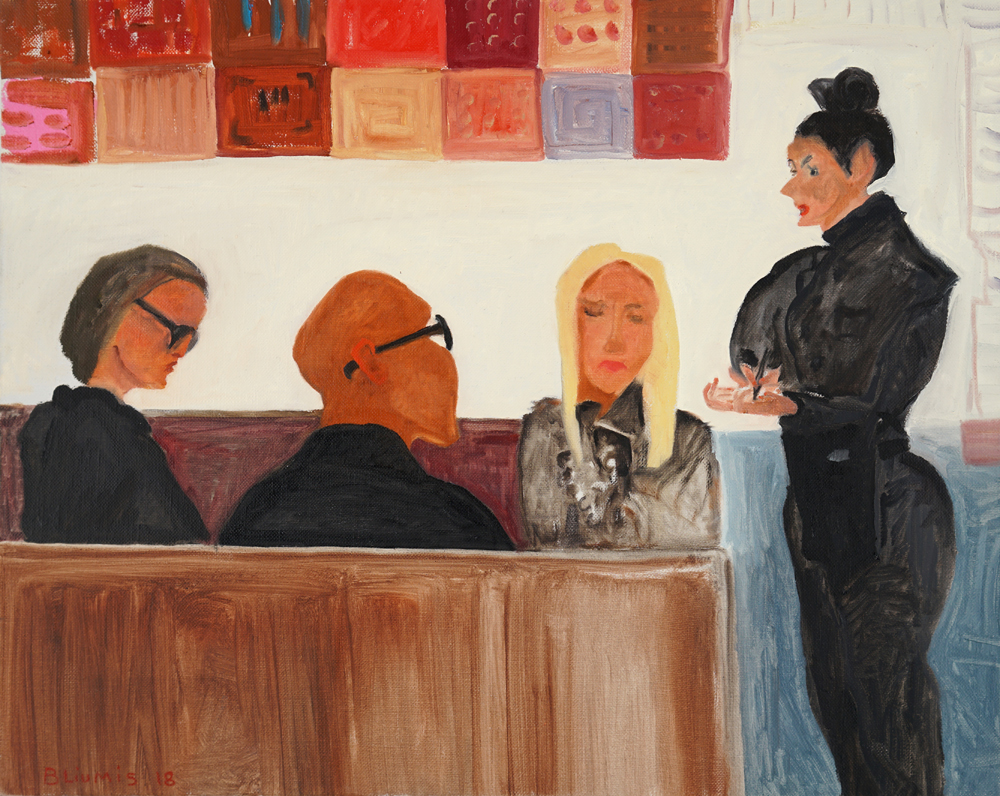

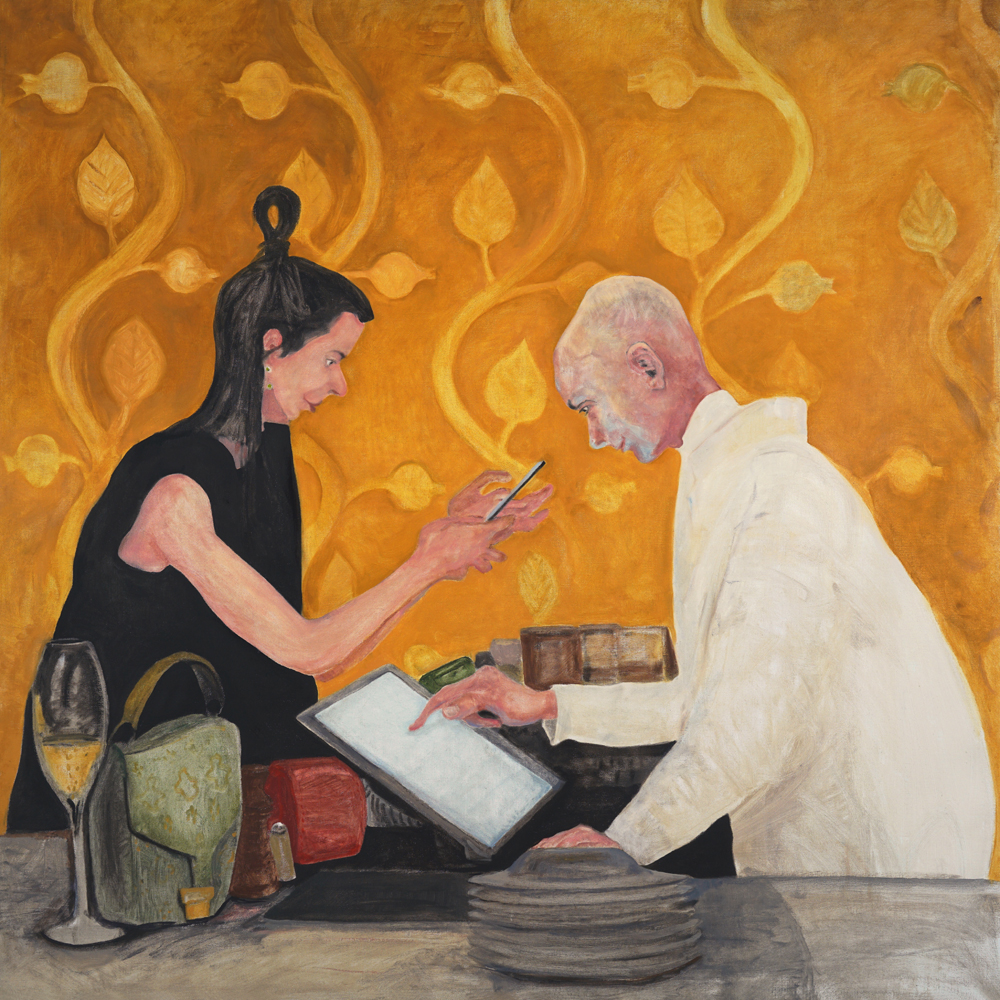

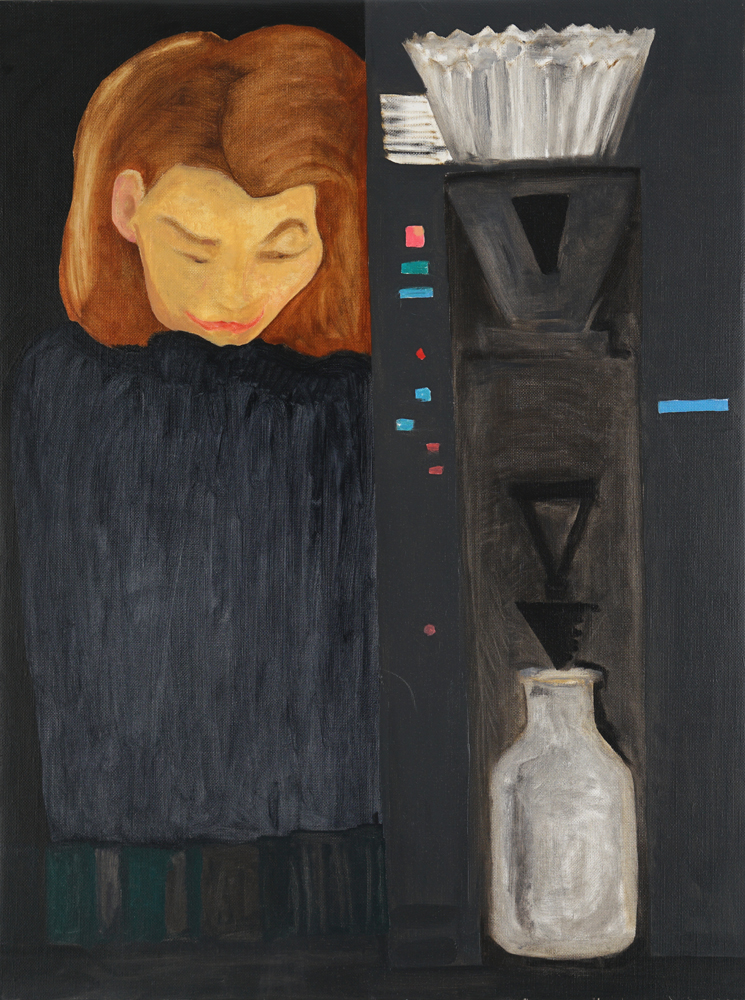

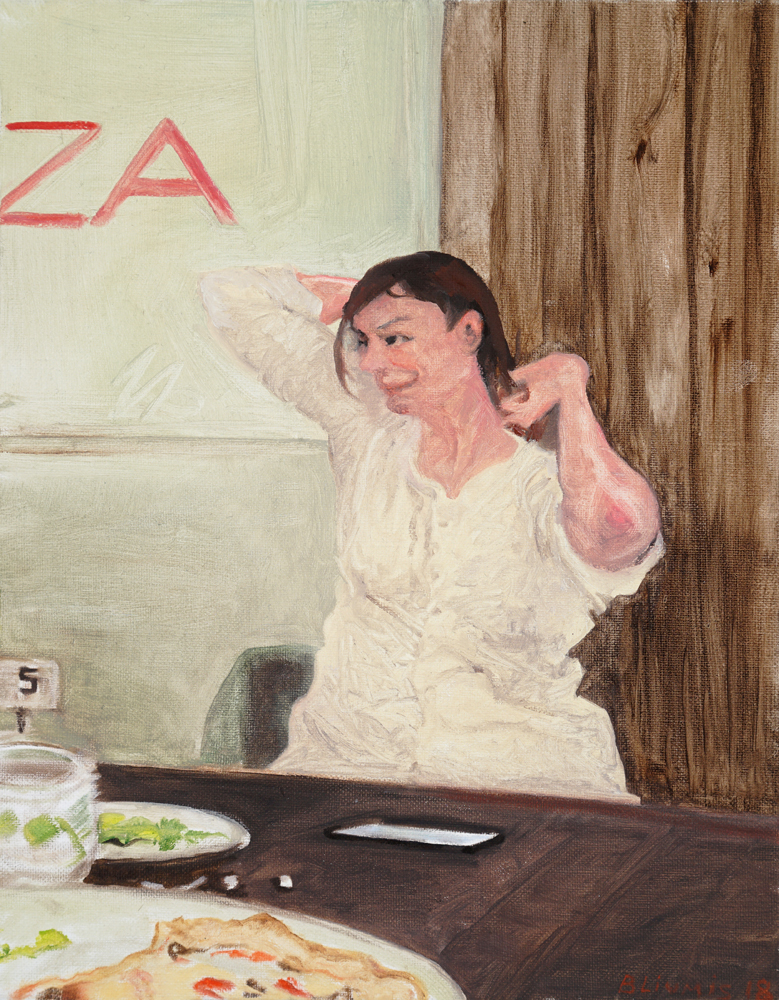

The works on show feature a wide cross-section of jobs and individuals. We meet bartenders, baristas, kitchen staff and waitresses, a restaurant hostess and a masseuse, Uber drivers and souschefs.

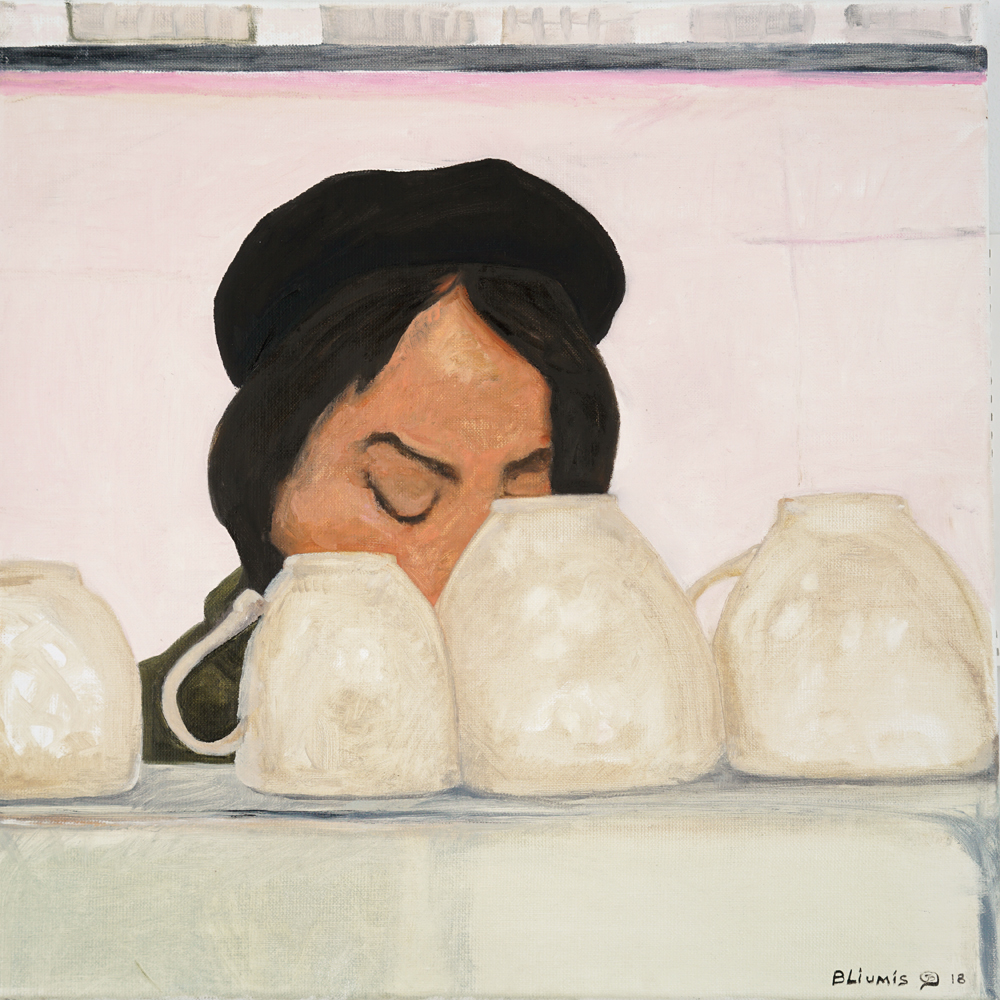

There is a scene from an airport waiting area and a person behind a coffee stand. But not only does the artist show these people from afar — observed at a distance much as we, the viewers, would likely do if we were there — he also cuts out much of their body and form, relegating them to the background.

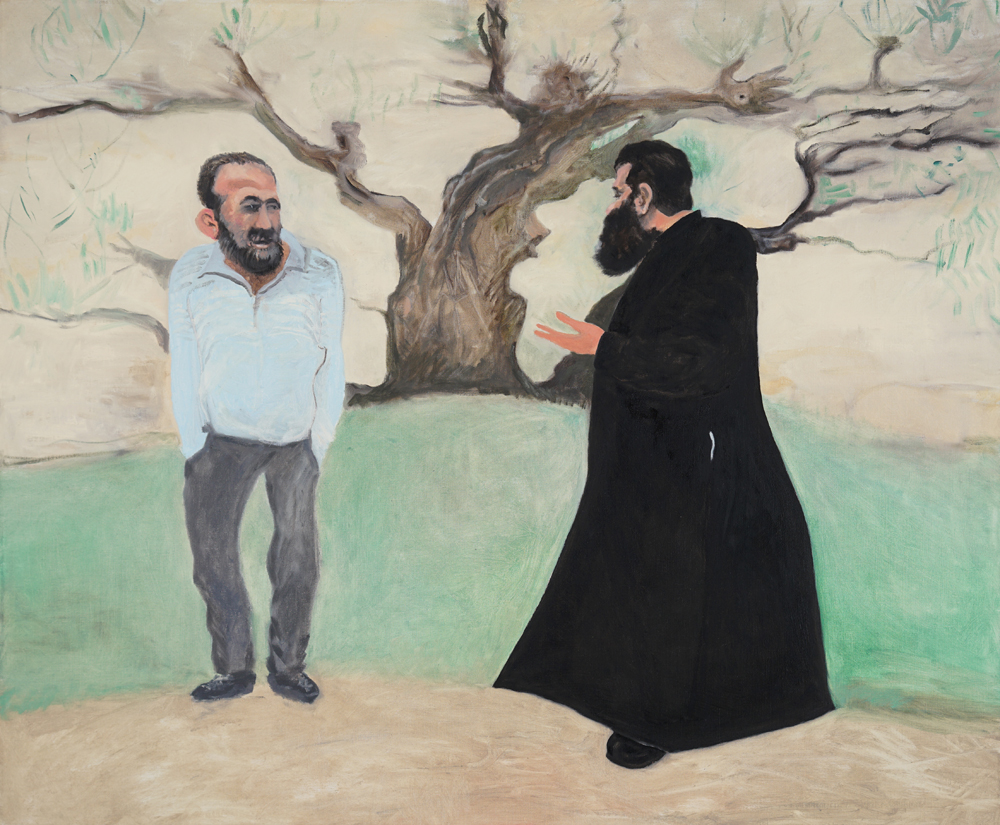

The exhibition includes paintings made from 2015 until today, and they are grouped into five series: Service, Jamaican Dining, American Dining, View From Below and Pilgrim State. Each series gives us a different perspective on Bliumis’ daily life in the city, and the people he encounters and pays attention to.

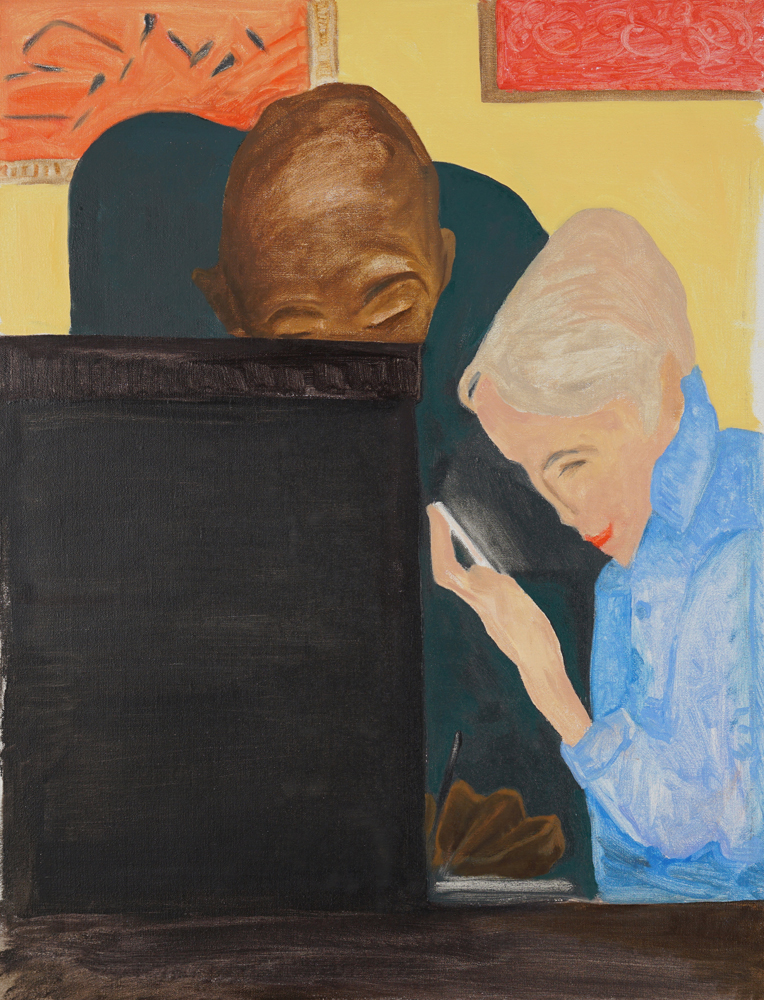

In AmEx, Small Order, Uber Ride, Blue Ribbon, Alex, Americano, 2018 he paints the quotidian scenes of their work places. They each have a personal touch. Looking at them gives one the sense of going through someone’s visual diary or their social media photo collection.

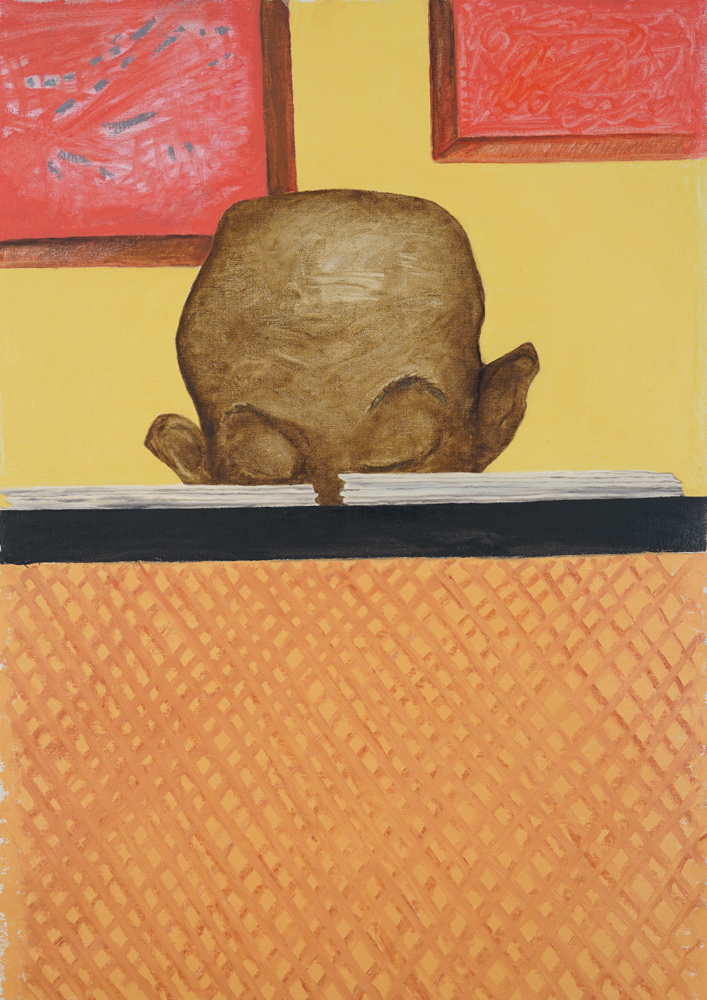

The people he paints are often partially obscured, or depicted with their backs toward the viewer. In About, Barista and Serge, 2018, only the tops of the subjects’ heads are visible behind a counter.

In Serge, almost half of the painting is taken up with a detail of a desk or a coffee counter, dotted papers, competing with a partial view of a bald, dark skinned man above. We see Serge’s downcast eyes and prominent ears against the background of a bright yellow wall, on which we see the corners of some red paintings. And yet, even though this is not his portrait, I am sure I would recognize Serge if I visited his workplace.

It is all these authentic details, set amidst his oblique viewpoints, which make his paintings so compelling: the gestures, poses, outfits, interiors and random food and drink items. Bliumis makes the mundane fascinating. In the process, he re-invents genre painting.

If the Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel defined the approach for scenes of rural and peasant life, Bliumis has taken ownership of genre paintings of modern, urban life.

The art historian, curator and writer Raphy Sarkissian recently compared and contextualized the artist’s paintings with the works of John Currin, Gustave Caillebotte and Max Beckman, among others. Writing in Whitehot Magazine, in a piece marking Bliumis’ solo presentation at the Spring Break Art Show 2019 in New York, Sarkissian described the experience of viewing his work as “irrefutably poignant.”

The impetus for reviewing his work through an art history lens also came from the fact that the photographer Andres Serrano — famous or infamous, depending on your point of view, for his aestheticized shots of urine, semen and blood — curated Bliumis’ presentation. There is a clear crossover in their work.

With his Residents of New York series, focusing on the city’s homeless, Serrano is plowing the same furrow as Bliumis. “Andres Serrano Wants New Yorkers To Stop Ignoring the Homeless,” was the headline on an Artnet piece about the series. Both artists are telling us to notice the ‘invisible’ people of our modern world.

For myself, as someone born and brought up in the former Soviet state of Georgia, Bliumis’ paintings also conjure comparisons with the work of the late Soviet writer and satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko. His short stories about daily life were popular both with proletarian audiences and literary high society of the time.

Similarly, Bliumis’ paintings have won praise both from the New York Times art section1 and regular New Yorkers. In Zoshchenko’s short story Poverty, the introduction of electric light turns out to be double-edged, because it shows up the dirt and drabness of the communal apartments in which people live.

Bliumis is giving us a choice too: prompting us to take a closer look at the drivers, waiters, cooks, cleaners and nurses who keep the world running. Or we can move on and disconnect. As Zoshchenko put it: “Electric light is good, it’s just no good to live with.”

1 Roberta Smith, Armory Fair Week: Your Survival Guide, Art and Design section, The New York Times, March 8, 2019